The Virginia House of Delegates is the oldest continuous English-speaking representative legislative assembly in the Western Hemisphere. Late last month, the Sully District Council of Citizens Associations hosted its Eleventh Biennial State Legislative Candidates Night, providing an opportunity for citizens of Fairfax County’s Sully District to ask questions of the candidates seeking to be elected or re-elected in Sully’s legislative districts.

As is often the case during election season, public education was an issue touched on by numerous candidates, both in their opening statements, as well as in response to public questions. A number of candidates—particularly non-incumbents—raised concerns that Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) are underperforming, noting that the system is “failing local students”. Several also raised concerns that administrative spending within FCPS, and within government more broadly, is too high.

Despite their assertions, the evidence presented was thin. Beyond limited anecdotes, no concrete data or analysis was offered to demonstrate inefficiency or underperformance. Some candidates even suggested that consultants should be hired to identify waste and inefficiencies.

The responsibility of government: providing evidence for the value-for-money of public services

The call for efficiency is entirely valid. Governments, like households and businesses, must strive to use limited resources as effectively as possible. But the idea that efficiency can only be uncovered by outside consultants misses a central point: ensuring value-for-money—and communicating the efficient use of public resources—is a fundamental part of the social contract, and thus, a fundamental responsibility of government itself.

Two principles are at stake here. First, governments “of the people, for the people, by the people” have a duty to perform their own due diligence to ensure that they are providing the highest possible value to their constituents. Second, representative governments have an equally important responsibility to communicate their performance clearly to the people, who are not just subjects of a monarch or passive recipients of public services, but as taxpayers and voters, the ultimate shareholders of governments at each level. Constituents therefore need to see not only how their tax dollars are being spent, but also whether those expenditures are producing equitable, high-quality services.

These principles are often framed as the need for governments to be transparent. This is an unwelcome simplification. At all levels, the American public sector is among the most transparent in the world. Citizens enjoy unparalleled access to raw financial and operational data. Both the Commonwealth of Virginia as well as Fairfax County, for example, maintain a wealth of open data portals, budget documents, and performance dashboards.

Where governments often fall short, however, is in transforming this data into evidence-based information that is meaningful to the public. Raw data is rarely self-explanatory. Without context, interpretation, and communication, figures on spending and staffing can be misused or misunderstood. This failure to convert transparent data into public understanding has contributed to the erosion of trust between citizens and their governments.

Looking at the numbers

To move past anecdotes, it helps to anchor the policy questions of the efficiency and performance of public education in Fairfax in an analysis of public expenditure data.

Some of this analysis is already available in previous posts on The State of Fairfax. For instance, an analysis of school division spending and performance suggests that while Fairfax County appears to be a “high-performing, high-spending” school division in nominal terms, when considered in real terms (i.e., after adjusting for the high cost of living in Fairfax County), FCPS is revealed to be a relatively high-performing and low-spending school division when expressed in real terms. Similarly, while Fairfax County is among the school divisions with the highest nominal teacher salaries, once teacher salaries are adjusted for the high cost of living, Fairfax County teachers rank 80th in terms of real average teacher salaries in the commonwealth.

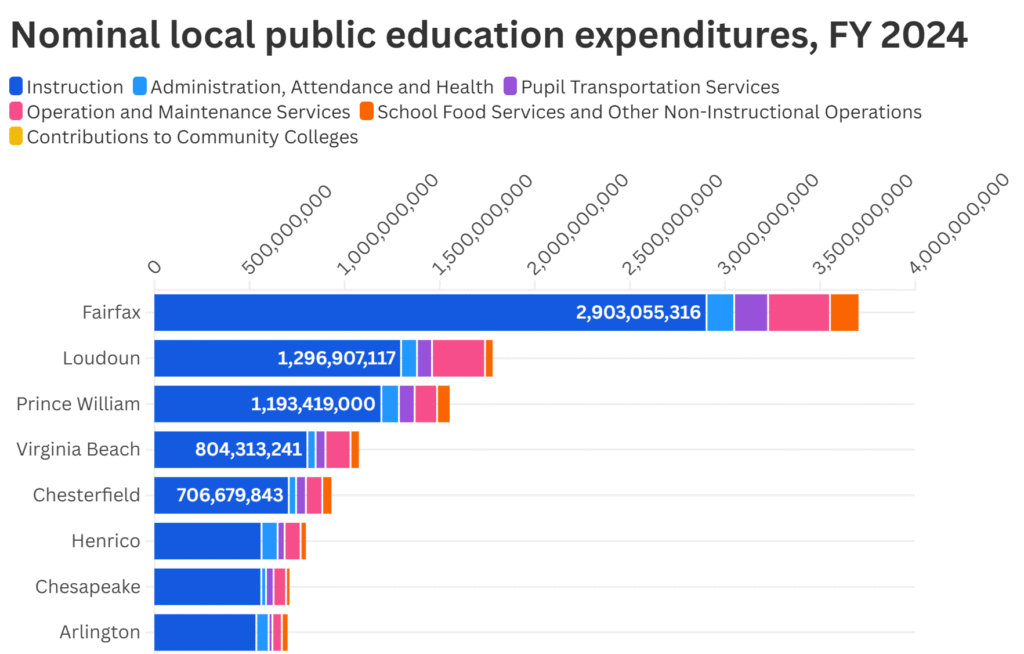

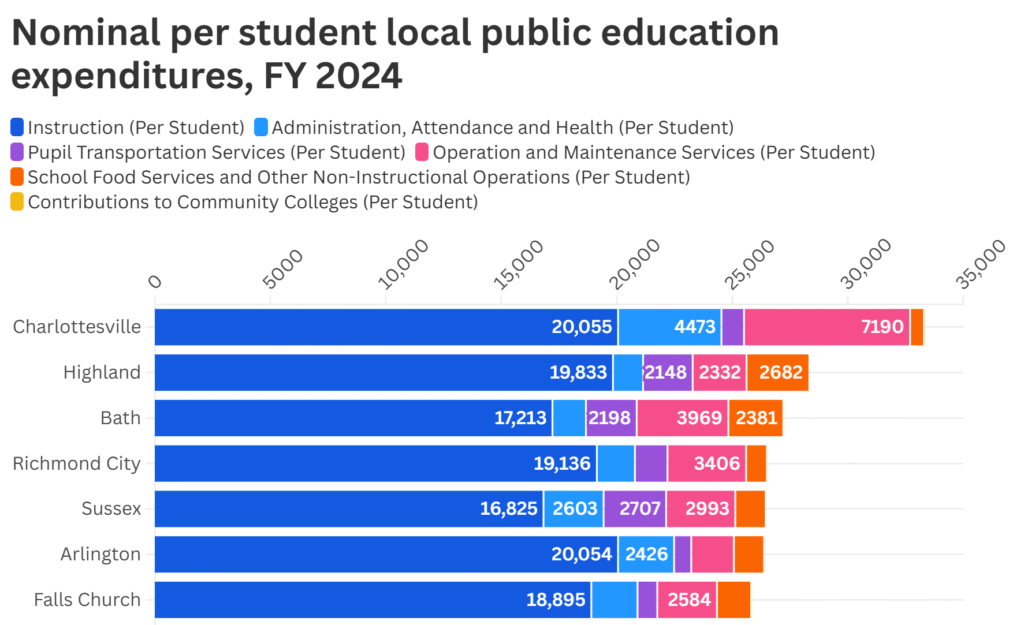

The current blog add to our collective understanding of the State of Fairfax (and the Commonwealth of Virginia) by considering public education expenditures in a comparative context, based on data published by the Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts for Fiscal Year 2024. Highlights are provided in the two images below. A full set of bar graphs presenting public education expenditures for all school divisions in Virginia (excluding those who failed to report data) are available in a separate post in the ‘Graphs and Maps’ section of The State of Fairfax.

Total public education spending versus per-student spending

Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) is the state’s largest division by population and enrolment, educating about 172,422 students. Unsurprisingly, FCPS also has the largest total local K–12 outlay—about $3.7 billion in FY 2024. Scale matters: big systems will always dominate totals.

What matters for efficiency is per-student spending, where Fairfax is not an outlier. FCPS’ nominal per-student spending is about $21,470 per student, which places it roughly 18th highest out of the divisions reporting per-student totals—higher than average, but far from the top tier of small, high-spending districts.

In fact, when we adjust for the per-student spending of FCPS for Northern Virginia’s high cost of living, the picture flips: cost-adjusted per-student spending is about $14,793, dropping Fairfax to roughly the 89th position—below the statewide median on a real-resources basis. In other words, once prices are normalized, Fairfax is not a big spender per student.

What the money buys: the spending mix

The composition of FCPS’ spending is consistent with a classroom-first allocation. Instruction accounts for about 78.4% of total outlays, well above the statewide median instructional share (which is around 71.8%). By contrast, administration absorbs about 3.9%, markedly below the statewide median administrative share (roughly 5.6%). Among divisions with comparable data, that places FCPS towards the bottom of the list for administrative overhead share. This is not what “bloated school bureaucracy” looks like.

Why cost-adjustment matters

Nominal dollars can mislead in a high-cost labor market. Fairfax must recruit and retain teachers, bus drivers, custodians, and specialists in one of the most expensive regions in the state. Put plainly: Fairfax pays more per dollar to buy the same unit of service (a teacher hour, a bus route, a maintenance contract). Real-terms adjustment corrects for that, and it shows FCPS is not operating with outsized resources. When we adjust spending for local prices (using the cost-of-living index constructed based on county-level cost of living data prepared by the Economic Policy Institute), FCPS’ real per-student resources fall into the lower half statewide—far from any narrative of over-investment.

Efficiency signals

Taken together, the comparative analysis provides three signals that cut against the claim of systemic inefficiency. These include, first, a high share of instructional spending (around 78.4%)—money prioritized for teaching and direct student support; second, a low share of administrative spending (3.9%)—among the lowest in the state, both as a share and per-student dollars; and third, a cost-adjusted per-student rank in the lower half—indicating Fairfax spends less in real terms per student on public education than many peers once prices are normalized.

None of this proves that every dollar is perfectly spent—spending in no large organization ever is—but the burden of proof for “bloated administration” or “runaway spending” is not met by the data. If anything, the data suggest Fairfax is channeling an unusually large portion of its budget to instruction while operating under higher input prices that erode nominal spending power.

This does not mean that Fairfax schools are beyond critique. Achievement gaps remain, particularly for students from low-income households, English language learners, and students with disabilities. These are serious challenges, and they require serious responses. But those concerns are about educational outcomes, not financial inefficiency. Conflating the two risks distracting from the real work of improving equity and performance.

The constructive conversation, then, should focus less on hiring consultants to “find waste” and more on (i) transparent, public-facing performance dashboards that link dollars to outcomes, and (ii) cost-aware strategies—procurement, staffing pipelines, and facility utilization—that stretch the real value of each dollar in a high-cost region.

Reframing the public discussion of the efficiency of public spending

The larger lesson from this debate is about how we, as the local level—citizens and elected representatives alike—talk about government performance. Transparency in government spending is abundant in Virginia, but evidence-based narratives are scarce. It is likely that, in many cases, claims of inefficiency or waste are deployed for political effect, unsupported by analysis. When unsupported by evidence, however, the impact of such claims is to fray the trust and the social contract that our communities and our local public sector are built on.

Meanwhile, governments themselves are not doing enough to convert their raw data into clear, compelling information about the value for money they provide. FCPS is not helping itself when it makes claims that it “cannot continue to sustain excellence with ongoing underfunding and budget cuts” without presenting clear evidence that it doing a good job with the resources it has.

The result is a vacuum of understanding—one that gets filled with suspicion and anecdote rather than evidence. If we want a more constructive debate about the efficiency and effectiveness of public education, the burden is on both sides. On one hand, responsible citizens and candidates must ground their critiques of public sector spending in evidence, not anecdotes. On the other hand, responsible and accountable government entities—as stewards of the public’s resources—must do go beyond making data available, and must become better at measuring and communicating its performance, turning transparency into real public accountability.

Note: The Feature Image for this blog post is AI generated.