For over a quarter of a century, the radio journalist Kojo Nnamdi has been a fixture in the DMV.

While The Kojo Nnamdi Show aired its final episode in 2021, Kojo continues to host The Politics Hour with Kojo Nnamdi each Friday with resident analyst Tom Sherwood, maintaining a vital forum for the public to engage with and hold elected public officials accountable.

On October 3, 2025, Kojo and Tom spoke with Loudoun County Board of Supervisors Chair Phyllis Randall about what a federal shutdown means for her residents, as well as the politically tense relationship between Loudoun County and both the current federal administration in Washington as well as Governor Youngkin’s Office in Richmond.

During the interview, Tom Sherwood noted that Northern Virginia serves as the cash cow of the Commonwealth, and asked Chair Randall how much funding Loudoun County sends to Richmond each year. Unfortunately, but understandably, Chair Randall didn’t have the exact number at her fingertips during the interview.

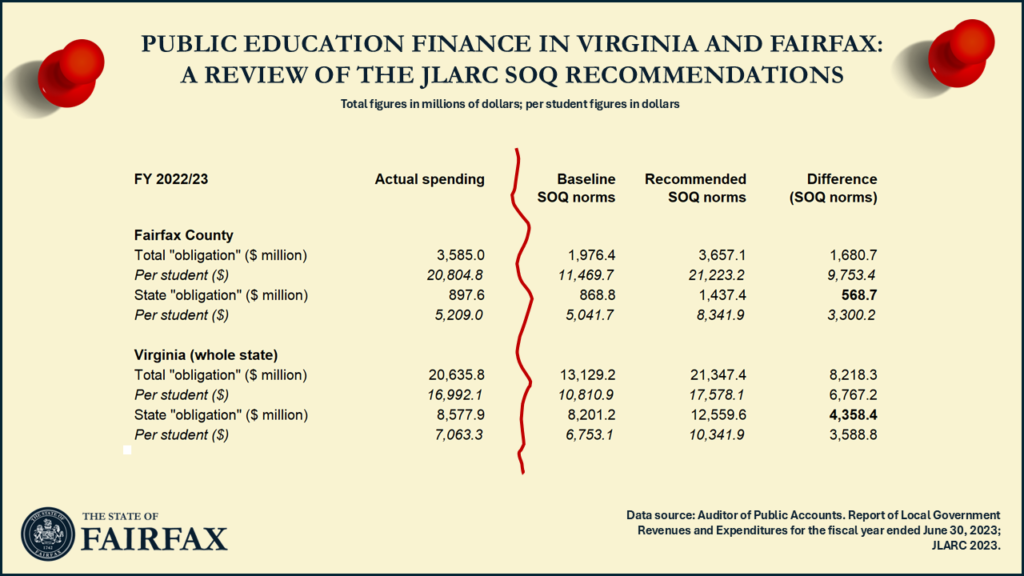

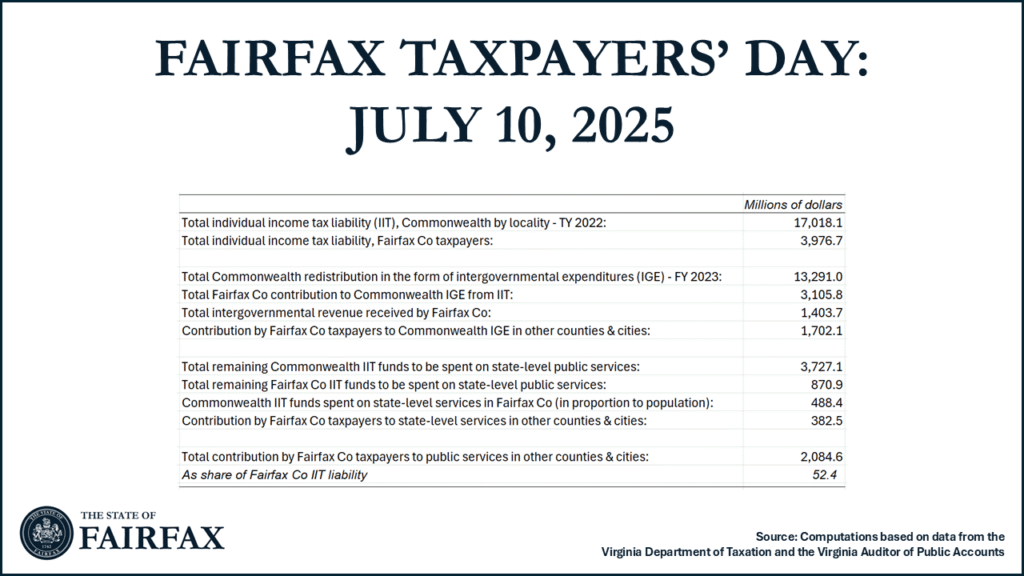

Given that I prepared a ballpark estimate of the Balance of Payment’s between Fairfax County and Richmond just days ago, I was able to use the same methodology to quickly compute the Balance of Payments amount for Loudoun County.

As shown in the attached computation (Excel, 22 KB), my back-of-envelope calculations for FY2024 show that Loudoun County taxpayers are sending roughly $809 million more to Richmond each year than county residents receive back in intergovernmental grants and direct state services.

For context, $809 million dollars per year is real money, even for a county touted as having the highest median household income in the country. This amount represents an annual net payment by each Loudoun residents of over $1,800 per person, or a net contribution per family (or household) to the Commonwealth budget of over $5,400 per year. That is ‘surplus tax’ on the Loudoun County economy and money paid by Loudoun County taxpayers that is sent to Richmond, and never comes back.

For comparison, the total balance of payments for Fairfax County roughly negative $2.5 million – roughly in the same ballpark, after accounting for the fact that Fairfax’s population is 2.5 larger than Loudoun’s population.

As I note in the original blog post, while fiscal redistribution is both expected and justified in a state intergovernmental finance system, the scale of the imbalance raises a concern. If one region in the Commonwealth continually gives far more than it receives, while also shouldering the challenges of rapid growth, infrastructure stress, and service demands –especially while at the same time being on the receiving end of non-stop political abuse from state leaders of the opposing party—then fairness becomes more than a rhetorical question.

As such, the debate is not whether localities in Northern Virginia should contribute to the broader commonwealth. They already do, generously and consistently. The question is whether the current fiscal arrangement fairly recognizes Northern Virginia’s needs as a community, its role as the state’s economic engine, and its right to a proportional return on the investments made by its taxpayers. In the end, fiscal balance is not just about numbers. It is about whether the bonds of the commonwealth are strengthened or strained by the way in which resources are collected and redistributed.